Nordic urban-rural typology

Esa Östring

22.06.2022

Introduction

Traditionally most classifications aiming to distinguish the urban from rural have been based on administrative boundaries. Such classifications are not without shortcomings, since there likely are both rural and urban land uses within a single administrative unit, the delineation practices of which also vary from country to country. To overcome this limitation, more detailed data can be used to distinguish urban and rural areas. This approach was taken by the Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) in 2013, when it first published a Finnish urban-rural typology based on geospatial data. Their sophisticated method created seven typology classes:

- Inner urban areas

- Outer urban areas

- Peri-urban areas

- Local centers in urban areas

- Rural areas close to urban

- Rural heartland areas

- Sparsely populated rural areas

Since then, this typology has been revisited and refined, and has been used rather broadly in different applications from planning to administration to statistical analysis and monitoring.

Problem statement for this work

In cooperation with Nordregio, our main goal was to form an urban-rural typology for all Nordic countries, using only open, free-of-charge data. In order to solve this problem, it was clear that we should first try to solve the typology mapping in Finland, where we had SYKE’s reference classification available. It was clear early in the process that the original 250m resolution grid data was not attainable as open data only, since most open national data is available in a 1 km resolution. The 250 m resolution would be also too detailed for this problem, since we assumably would need to make some simplifications to the original SYKE approach in our work.

Initially, there was no strict reference grid preference. Two obvious approaches were considered, namely using Eurostat’s grid (EPSG:3045) for all countries. This approach would result in all countries having a uniform grid, without discontinuities on country borders. The other alternative was to represent each country in its own national grid. Then, the classification would be more suitable and familiar for further use in each country individually. Also, some of the input data was already available in aggregated form for national grids. Nevertheless, it is good to mention that we created a grid agnostic process, easily reproducible for any arbitrary grid.

Modeling approach

It was agreed that the modeling be conducted using both traditional GIS methods and machine learning. Having some overlap in the modeling, we could painlessly review methods and results, and favor the methods producing better results. Traditional GIS methods would provide a firm background with less of a risk: it is not likely that these would fail completely. On the other hand, machine learning could provide substantial benefits, but the risks in implementation were greater: are we able to find reasonably well behaving methods for our problem? Altogether the challenge is still there – can we model an urban-rural typology with open and free-of-charge data in the Nordic context?

Classification experiments – where to focus

Initially we thought that the urban typology classes would be easier to predict from available data than rural ones. So the main challenge would lie in detecting different types of rural areas, and this led us to experiment with a Random Forest classifier. We taught the classifier only forrural heartland areasin the Finnish context. The results were so promising (not perfect, though) that we immediately broadened the scope and included all classes in the classification.

All classes - classification experiment

By visual inspection, the results from an all-classes Random Forest classification experiment were rather well performing. Misclassifications were present, but the general big picture was satisfactory, very similar to the SYKE original. It was also quite clear that small isolated errors in classification are tolerable and those errors can be mitigated in the later phases of the work. Data we used at this stage were:

- Total population in 1km grid cell

- Amount of “low” buildings in 1km grid cell

- Amount of “tall” buildings in 1km grid cell

- Amount of unknown buildings in 1km grid cell

Systematic classification errors happened inside larger lakes. Misclassified areas typically had nonexistent populations or buildings. It was obvious that we needed a variable for land use to obtain a more reliable classification. Our incremental design approach allowed us to experiment with and adapt the model easily for land use data as well. European Corine Land Cover (CLC) data contains 44 land use classes, hierarchically structured. We utilized the most exact land cover classification and generalized the data into our 1 km grids. All land cover types were not necessarily present in all countries, which required exception handling. If there was a land use variable present in a country but not in the model, this feature was dropped out.

Image 1. Random Forest classified urban-rural typology in Finland (random color scheme).

Country considerations

Since the model was fitted using Finnish data, it was still unknown how the model would perform in other countries. Before finding this out, it was necessary to gather source data and compute aggregates for other countries. Gathering data from all countries was an interesting mission: We faced multiple problems or at least open questions, with some being:

- Documentation of the data was not always up to date

- Reality and documentation did not meet in many cases for data access

- API limitations (and errors) when fetching data for a whole country

- Countries have very different policies about data pricing

- Differing data classifications (especially for buildings)

- Availability (or lack) of data.

- Metadata documentation not up to date or missing

- Challenging to specify a temporal dimension for data (e.g. a specific year) consistently

- Challenging to find the best way to obtain data

- Sometimes manual human effort is required to download the data (vs. API access).

Data

The work started by obtaining spatial grids for each country. 1 km grids were already gathered by Nordregio, and we could proceed with other data. CLC was easily processed for all countries. Population data was mainly readily provided by Nordregio. During the classification process we demonstrated multiple methods to produce updates from municipal population statistics, disaggregated to a grid level. These experiments didn’t make it to our final analysis, but provided the capability to estimate grid-level population from annual municipal population statistics. This capability also allows later classifications in arbitrary grids, if need arises.

Building data in the Nordic countries is by no means uniform, and the classification we chose is rather coarse, but it gets the job done. Building data fell into three different categories based on the number of floors. In Iceland our estimate of building classes is probably the most inaccurate. This is based on the fact that we had to estimate classification of building data from OSM since there was no free national building data available. The OSM classification is not very fine grained, and potentially differs between similar buildings. There is of course a benefit in using OSM data: we could now easily reproduce this building classification for other countries as well.

Some of the data used in the end was based on grid cell neighborhood statistics based on a better explanatory power. This was the case for population and building data.

Classifying two rural classes – approaching final classification

While an all-classes classification with Random Forest proved its strength, we wanted a bit more control on the final classification by developing a two-class rural classifier. This would provide a uniform countrywide canvas, consisting of rural heartland and sparsely populated rural classes. On top of this canvas we would compute all other typologies with traditional GIS methods. The model learning material had to be tweaked a bit - by including the urban areas inside rural ones, thus being able to create a continuous canvas without gaps, on top of which the real urban classes could be overlaid.

Image 2. A two-class typology with everything some sort of rural (either core rural areas in yellow, or sparsely populated in green)!

Detecting urban centers

Urban center detection was done with a separate classifier, which was fit in Finland using SYKE reference data. Original urban center source data was aggregated to a 1km grid, and the result was used in fitting the classifier. Grid cell population and building data were used in the model as features, and Random Forest was used once again. The method resulted in contiguous urban centers with a population of 15000 inhabitants or more.

Image 3. Urban center classifier results in Norway (brown area representing classifier results, orange ones small localities or potential outliers. Dark red represents the official Norwegian "urban center" or Tätort delineations.

Travel-time considerations

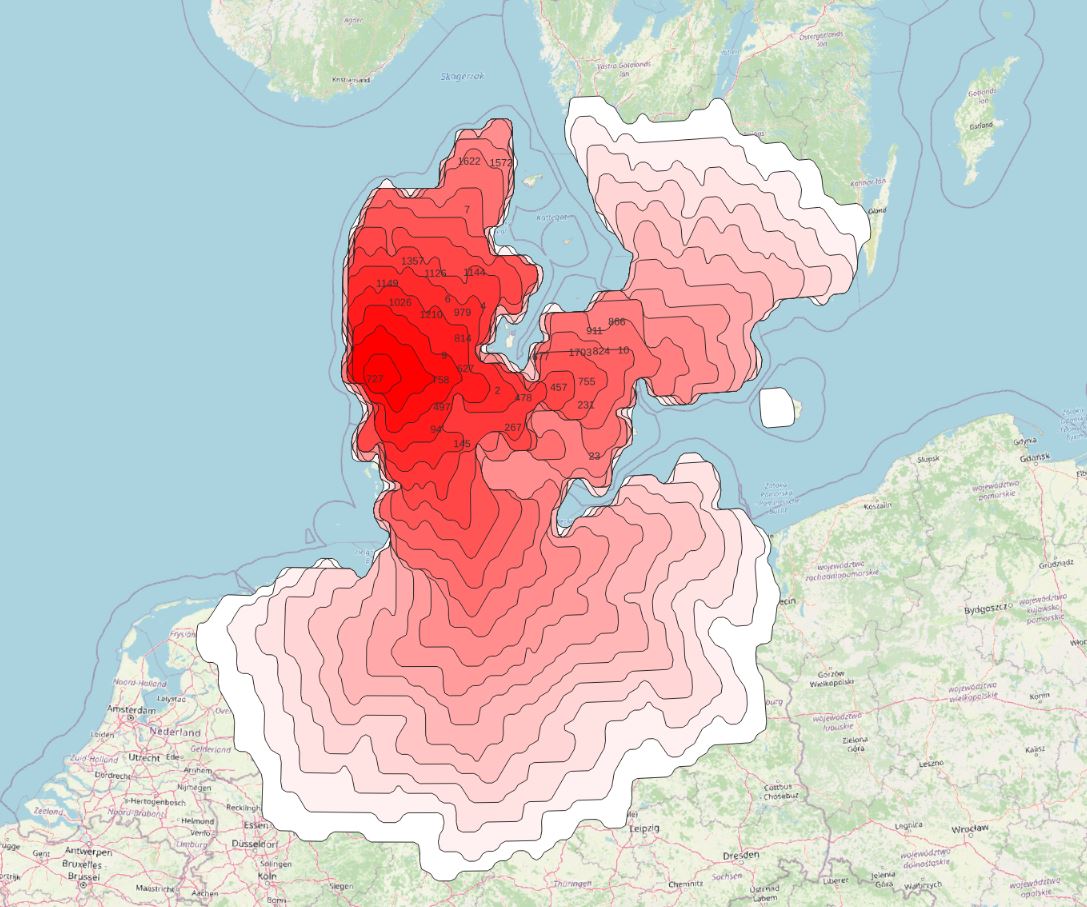

The original SYKE typology models labor movement from commuting data and economical structures described by Herfindahl index. This was not attainable in the Nordic countries based on open data. We decided to examine two approaches: Huff gravity modeling for each center, and a fallback approach, isochrone travel time computation modeling urban center reachability. The Huff model would compare urban centers and their relative attractivity compared to other centers. Experiments were done for Denmark, but computations were unnecessarily time consuming, and there wasn’t enough performance gain to support the extra complexity.

Image 4. Doing some testing for a Huff gravitational analysis in Denmark...

We then ended up proxying missing travel-time data with isochrone computations. Each urban center was extended by specific travel time intervals. Outer urban border and road network intersections were found, travel times computed from each point, and isochrone geometries dissolved by travel-time.

Image 5. Travel-time isochrones laid on top of rural classifications.

Image 6. Nordic urban travel-time isochrones.

Repeatability considerations

Instead of obtaining only a one-off classification for all Nordic countries, we still had an additional requirement of repeatability. The classification should ideally be easily repeatable whenever data changes. So far we have been documenting the process. Some considerations still exist. Next steps in streamlining the computation process could be:

- Combining different SQL computations

- Reducing resulting database tables

- Refactor some code as native Python code

- Unify country specific computations: utilize country specific configurations and refactor code to be more generic and accept configurations as input.

- Consider unifying the used tool base, or at least try to minimize number of tooling interfaces during computation

Used tools and methods

Data preparation was mainly done with SQL. Source data was uploaded to the database, and data enrichment results were stored in the database. We found out that it is nice to have at least some of the source data in a standardized table, regardless of the country (geometries, population and building statistics). National differences in data were harmonized to a common schema. The computations from a unified schema were naturally a lot easier.

When there was a need to process the data even further (beyond SQL comfort zone), Python was used. The classifier was programmed in Python, using the RandomForest classifier and variable scaler from sklearn package. Some steps required travel time computations (isochrones), where open source Graphhopper was used as a local containerized service. An individual service was set up for each country, due to separate routing materials from binary OSM exports. For the sake of comparison, HERE Isochrone API was also tested. Both produced similar results. Some effort had to be taken to convert differing results to a common internal representation. Our implementation is written to be “router agnostic”, so it is a matter of configuration which isochrone computation engine is used.

Finally, we used FME for some end processing, data clean-up and publishing pipelines, for now, at least.

Now, the Nordic urban-rural typology is open for comments and shakeholder scrutiny (and probably some refinement), before it’ll be used in practical applications. Go check the draft yourself online here: https://nordictypology.ubihub.io/

Image 7. A first look on the draft Nordic urban-rural typology.